Whom can you trust?

Trust has been a thorny issue in human affairs—arguably for all of human history. From the tragedy “Medea” of Euripides to the infamous “

et tu, Brute?” uttered by Julius Caesar, trust and betrayal have been a mainstay of drama in fiction and in real life.

In our modern era, there have been persistent declines in trust across the world—from the deteriorating faith in government in many OECD countries and the trust crisis in Latin America to rising mistrust among citizens of the United States. And that was even before the COVID-19 crisis changed everything.

For a quick take on how much has changed since the virus began its global spread, try reaching out to shake hands with someone or imagine someone reaching out to shake hands with you. Up until early 2020, this gesture was the default greeting in much of the world— attracting attention only when it took the form of a naked power play. So indicative was it of trust that the humble handshake was used to signal the resolution of an argument, a return to friendly relations.

Now, in the era of COVID-19, this age-old gesture has become taboo. Seeing people shake hands in pre-2020 movies or news videos can feel jarring. It looks “wrong,” dangerous even. Dr. Gregory Poland, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in the U.S., has described the outreached hand as “a bioweapon”—a description that may sound like a gross exaggeration until one sees an online demonstration of how germ-laden hands can be. Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said he would be happy if people quit shaking hands altogether to slow the spread not just of COVID-19 but also of other infectious diseases such as influenza.

The demise of the handshake illustrates our enforced break with the old “normal” and speaks to our newfound fear of those around us. In 2020, the only people with whom most of us feel comfortable “pressing the flesh” are members of our households. We cannot trust our intuition or rely on spotting familiar signs of illness such as a cough or rash because so many carriers display no symptoms and likely do not even realize they are contagious. So, we have to mistrust everybody. We have to act as if anybody may have the disease, including ourselves.

CONTENTS

- Whom can you trust?

- A simple word masking a complex concept

- Measuring trust: A worldview

- The erosion of everyday trust

- The perfect storm: Mistrust, conspiracy theories, and the web

- Reconciling progress and trust today

- Opportunities and expectations for a business to build trust

- Looking ahead: Resetting in business

From upset to reset

Trust in a COVID world

Adopting mistrust as our default response goes against the grain because people are trusting by nature. Trust runs like an invisible thread through the web of societies, holding things together—until it doesn’t. While tests and therapies and vaccines will be essential in protecting against the virus, the transition to a viable “new normal” will depend on restoring old threads of trust and weaving new ones.

Now, in the era of COVID-19, this age-old gesture has become taboo

This white paper explores issues of trust from several perspectives—historical, social, psychological, and contemporary. Drawing on quantitative insights from international surveys, it examines the broader implications of the pandemic on public trust and offers critical considerations for discussion as society strives to restore trust in this new environment. It also asks: What is expected of businesses in this process? As the business community works to adapt to our new realities and restart the economy, how should it act to fill the trust gaps that have been widened by the pandemic?

TRUST AND THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY

We understand that many people trust neither Philip Morris International (PMI) nor the tobacco industry in general. Therefore, even as we transform our business to deliver a smoke- free future—one in which those adults around the world who would otherwise continue to smoke instead switch to the better, smoke-free alternatives science and innovation have made available—we accept that earning trust will take time.

Rather than expect implicit trust, we ask that people examine the scientific evidence and objectively judge us on our actions instead of on any preconceived notions they may have. We encourage everyone—the scientific community, our customers, health authorities, and others—to draw conclusions based on open and transparent data related to our smoke-free alternatives. This is why we have published clear business transformation metrics and consistently communicate our progress toward achieving these objectives.

While our focus remains on hard science, we are keen to understand the foundation of trust given its reverberations within the broader societal debate around the potential that smoke-free products hold for men and women who currently smoke.

A simple word masking a complex concept

The word trust comes quickly to mind and rolls easily off the tongue. But what does it mean in practical terms? What does it mean to say: “I trust this person,” “I trust this organization,” or “I trust this information”? Attempting to pin down trust has long interested philosophers, who routinely debate its nature, rationality, and ethics. More recently, psychologists have brought their distinctive perspectives to bear on the issue and teased apart two types of trust: head and heart. Cognitive trust (head) is based on a person’s rational evaluation of knowledge and evidence. In contrast, affective trust (heart) is based on a person’s emotional belief in the care, concern, and good faith of whom they are being asked to trust. From a social perspective, there is the all-around generalized trust of society at large and the particularized trust that exists among familiar people such as friends and relatives.

However various communities define trust, in practical terms they all reach a similar conclusion: Trust makes social life simpler and safer.

However various communities define trust, in practical terms they all reach a similar conclusion: Trust makes social life simpler and safer. As Dr. David W. Miller, director of the Princeton University Faith & Work Initiative, and Dr. Michael J. Thate wrote in a 2020 white paper for PMI: “Our actions and interactions in society are guided along through a framework of trust, however latent, implicit, or subconscious it may be.” Trust is essential to the cooperative activities that make human life both livable and worth living, such as friendship and love, rearing children, and working with others. When trust is strong and nurtured, people need not waste valuable time and energy protecting themselves against being tricked. Imagine how different life would be if we were forced to assume that every person and organization with which we came in contact acted exclusively out of self- interest, with no regard for others. Instead we have devised ways—as individuals and collectively—to determine whether and to what extent we can extend our trust.

Consciously or not, when assessing the trustworthiness of an individual and entity, we tend to consider these questions:

- Competence: Are they good at doing what they are supposed to do? Do they have sufficient knowledge, abilities, and skills to fulfill their obligations?

- Integrity: Do they live up to their stated values and codes of conduct? Do they obey the laws covering their activities, as well as the law more generally?

- Transparency: Are they open about their intentions and methods? Do they say one thing in public and do something substantially different in private?

- Consistency: Do they reliably do what they claim to be doing? Do they do their best to deliver the same (or a better) standard of product every time?

- Honesty and accountability: Do they speak truthfully, in accord with established facts and information? Do they own up to their mistakes and accept responsibility for them? Are they willing to be held accountable?

One of the signs of our times is that many people don’t trust abstractions. We want concrete examples that illustrate an idea or a claim. We want ways to measure, quantify, and compare things to understand them better. Accordingly, the next sections of this report look at measured levels of trust around the world, before and after the COVID-19 pandemic took hold.

Measuring trust: A worldview

Volume, height, distance, weight, density, and speed are all metrics applied to objects in the physical world. They can be measured objectively. In contrast, trust does not exist in the physical world. It exists only in people’s minds and is manifested only in their behavior. Yet trust and mistrust are highly influential considerations in all human affairs. Consequently, polling companies, academics, and pundits have all devised ways of describing and measuring these factors.

Fluctuations and disparities in public trust are likely to continue as parts of the world endure a second (or third) wave of COVID-19, as the economic impact deepens, and as the world continues to navigate toward our collective post-pandemic reality.

As Miller and Thate wrote in their white paper: “Sectors as diverse as aerospace, automotive, banking, commodities, government, media, and even professional services that purport to serve a common good have betrayed the public trust. Through misdeeds and charges of obfuscation, falsification, malevolent lobbying, and disingenuous denials, they have ruptured trust. Even religious institutions have lost trust when their behaviors deviated starkly from their own social teachings.”

In its 2019 Radar report on levels of public trust in 25 countries, insights and strategy consultancy GlobeScan noted: “Global companies, national governments, and the press/media remain the worst-performing institutions in terms of public trust, all with declining ratings compared to 2017.” On the opposite end of the spectrum, GlobeScan found science/academic institutions, NGOs, and large charitable organizations to be among the most trusted, all showing “an increase in net trust from 2017 levels.” Taking a closer look at the increased trust in science and technology, the researchers stated: “The trend of rising trust in scientific institutions, combined with the decrease in trust in governments and business suggests that people are increasingly placing their faith in science and technology—in objective observers, rather than vested interests—to solve complicated challenges like climate change.”

This trend of increasing trust in science seems to be gaining momentum amid the current pandemic. According to the latest Reuters Institute Digital News Report, based on research conducted in April 2020, survey respondents in Argentina, Germany, South Korea, Spain, the U.K., and the U.S. ranked scientists and doctors as their most trusted source of news and information about COVID-19, with national health organizations coming in second.

Early signs of a surge in trust in governments as the pandemic began its spread suggested a potential reversal of fortune for political leaders. This trend proved temporary, however, as trust in government measures began to slide in some countries after weeks of lockdown restrictions and the related economic distress. A Kantar study on perceptions of COVID-19 in the G7 countries, published in June 2020, reported a decline of 9 percentage points since March in people’s trust that their governments would make the right decisions in the future.

Public confidence in politicians appears even lower. In its July 2020 COVID-19 Opinion Tracker, covering Germany, France, Japan, Sweden, the U.K., and the U.S., Kekst CNC noted that “political executives have come under severe pressure with the lowest performance assessments in each market surveyed with the stark exception of Angela Merkel in Germany.” Globally, domestic politicians are also seen as most responsible for the false and misleading information found online, according to the Reuters report.

This trend of increasing trust in science seems to be gaining momentum amid the current pandemic.

Business experienced a similar reversal of fortune, with Kekst CNC highlighting in its latest opinion tracker that “faith in business may be declining after a very strong performance in the first months of the pandemic.” According to the survey, the proportion of people who said that business was stepping up in their country was down in September compared with July, in France, Germany, and the U.K. In the U.S., the picture remained stable.

Fluctuations and disparities in public trust are likely to continue as parts of the world endure a second (or third) wave of COVID-19, as the economic impact deepens, and as the world continues to navigate toward our collective post-pandemic reality.

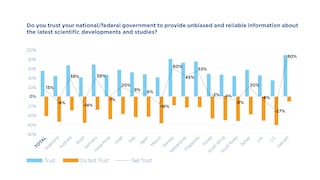

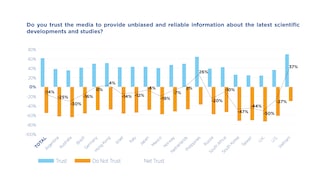

TRUST IN SOURCES OF SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION

The pandemic has created a pressing need to communicate scientific information to the public, reminding us how crucial it is for people to have access to facts that help them make informed decisions. But this can be a complicated endeavor, particularly when misinformation abounds and science has been tainted by politics. How are these dynamics impacting people’s trust in sources of scientific information?

In an international survey conducted for PMI by independent research firm Povaddo in summer 2020, respondents were asked how much they trust various sources to provide information about the latest scientific developments and findings. The survey covered 19,100 adults in 19 countries and territories across Europe, Asia, the Americas, and Africa.

Ministries or departments of health came out on top as most trusted, with around two-thirds of respondents trusting them completely or somewhat to provide unbiased and reliable scientific information. The World Health Organization and state/regional governments followed—trusted by 63 percent and 56 percent of respondents, respectively.

The least trusted sources were national/federal governments and the media.

The survey data also showed that, across the board, the public has more faith in institutions than in the politicians or individuals who represent them.

In the case of COVID-19, persistent misinformation regarding the virus is amplifying distrust among the public, in turn hindering compliance with lockdown measures and other social distancing policies. Making public health decisions openly and transparently—while sharing information in a consistent way—will be critical for governments seeking to build trust in institutions and leaders alike.

The erosion of everyday trust

Modern economies and lifestyles depend on countless instances of unspoken trust. Every time we purchase a product, we trust that the description is accurate. We trust the producer to ensure the product is free of dangerous ingredients or defects. For products such as food or medicine, especially, we trust that the production facility is clean. We trust that any official certification on the product is genuine. When we buy from strangers online, we trust they will provide the selected product and, in most cases, will issue a refund or replacement if the product isn’t satisfactory. Collectively, we conduct billions of dollars of transactions online each year and trust that we will not be defrauded.

In most of life, most of the time, this is how we move through most interactions: with implicit trust.

This fabric of trust is dense, but it has been wearing thin in places.

This everyday trust is based on fundamental assumptions that are affective rather than cognitive—things we feel rather than things we know. We assume there are laws and regulations protecting people against bad actors. We assume that authorities will ensure rules are respected and that any breaches are punished. We assume that organizations are keen to maintain their reputations and so act in accordance with laws and best practices. We assume that our fellow consumers and investors will pay attention rewarding organizations that act in trustworthy ways and shunning those that do not. For the most part, we are trusting because we have accumulated reasons to trust or—probably more important—have not been given reason to distrust.

This fabric of trust is dense, but it has been wearing thin in places. The media thrive on cautionary tales of people being duped. We hear about hacking, identity theft, phishing, ransomware, fake identities, and, of course, fake news.

Online review systems intended to enhance trust may instead introduce shadows of doubt. We may wonder whether the review is fair and accurate and reflects the balance of customers’ experiences. Maybe the brand encouraged friends and family to write glowing reviews or gave customers an incentive to do so? Maybe competitors posted unfairly negative reviews?

Against this already fragile backdrop, the COVID-19 pandemic—with all the uncertainty and fear it has engendered—has further complicated people’s decisions on whom and what to trust. Can we trust that the person shopping for groceries next to us has acted responsibly and does not carry the virus? Can we trust that the restaurant staff disinfected our table, cutlery, and menu before we arrived? Can we trust that all hygiene rules were followed by those who prepared our takeout food?

This global health crisis has accelerated our need for trust, even as we grapple with heightened levels of uncertainty. There are plenty of reasons to be wary, but being constantly mistrustful is hard work. It limits opportunities. How can we restore trust in everyday life?

The perfect storm: Mistrust, conspiracy theories and the web

In an ideal world, objective data can help people to shape ideas of the world that are accurate and verifiable. But society does not always work in this way. In fact, it mostly does not work in this way. In many instances, people treat facts as optional extras, cherry-picking among them to justify what they already believe. The online world offers endless support for confirmation bias, whereby people trust information that supports their existing beliefs and discount data points that challenge them.

In highly partisan nations especially, skepticism and mistrust of official information are expected. Digital channels of communication intensify this mistrust by providing a constantly replenished store of conspiracy theories, including narratives about insidious, powerful groups working in the shadows toward their own devious ends. People who give credence to such theories often don’t trust consensus explanations of powerful and tragic events. Rather, they dismiss official explanations as part of the conspiracy.

The internet and social media offer fertile ground in which such theories can thrive.

This appetite for conspiracy is widespread in our hyperconnected age, but it is not new. From Ancient Rome—where Emperor Nero was painted as the architect of the fire that destroyed much of the city—to the present, such theories have been omnipresent. The 1963 assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy inspired dozens such theories—as did the 1997 death of Diana, Princess of Wales, the 9/11 attacks, the disappearance of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370, and many other events, including COVID-19, which has proven a perfect petri dish for the spawning of a whole new slew of dark theories. This phenomenon is part of the human tendency to see patterns in apparently unrelated events (“patternicity”) and to think there are unseen agents making them happen (“agenticity”).

The internet and social media offer fertile ground in which such theories can thrive. Anybody who distrusts the official version of an event can easily find others online who will share and deepen their suspicions. The pandemic appears to be compounding this problem. According to a July 2020 report by the U.K.’s Commission for Countering Extremism (CCE), the global crisis has increased the visibility of anti-vaccine, anti-5G, and anti-minority conspiracy theories. The CCE forecast that “extremists will seek to capitalise on the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 to cause further long-term instability, fear and division” in the country.

Already in 2011, it was estimated that—because of the growth of the internet, 24-hour television, and use of mobile phones—the average person was receiving five times as much information as people did in 1986.

Fortunately, the public is not blind to the false information being seeded online. People know there is a lot of disinformation out there; they just don’t necessarily agree on how to classify each piece of “news.” So, which sources do most people trust? In general, the internet and social media networks garner much lower levels of trust compared with traditional media. The European Broadcasting Union noted in its Trust in Media 2020 report: “In 28 of 33 countries [across Europe], social networks are the media that people trust the least,” highlighting that “while social networks are widely used to get information about COVID-19, the gap between usage and the trust expressed is particularly high.”

The abundance of information and opinion available today is both a blessing and a curse. Already in 2011, it was estimated that—because of the growth of the internet, 24-hour television, and use of mobile phones—the average person was receiving five times as much information as people did in 1986. That’s equivalent to an extra 174 newspapers of information every day. Broadening our access to information has increased our collective knowledge and awareness. But in this sea of information, it is not uncommon for misinformation, conspiracy theories, or false allegations to be weaponized, moving the debate away from an objective discussion of the facts and merits of an argument. Handled correctly, the internet and social media can be channels through which to share facts, dampen speculation, tackle misconceptions, and, ultimately, rebuild trust. The question that is vexing social media companies, governments, academics, and concerned citizens is how to harness the positive potential of these channels while mitigating the risks.

Reconciling progress and trust today

Teasing out which sources to trust has been an integral component of many people’s experience of COVID-19. Despite the significant knowledge base scientists have built since the beginning of the year, this remains a puzzling new disease. No one can yet say with confidence how it will behave. Medical researchers have been scrambling to understand how it affects the body, what sorts of people are especially vulnerable, and why. Epidemiologists’ models of spread have varied widely, as have government responses: from tight lockdowns in China and New Zealand to strict surveillance and testing in South Korea, to the relaxed approach initially taken by Sweden. The only thing that seems certain is that we will be grappling with the virus for some time to come.

Whatever actions health authorities, experts, and politicians take regarding the pandemic, they will have a tough job earning broad trust among their citizens, especially in nations where people are politically or culturally polarized. As health and economics statistics emerge through 2020 and beyond, there will be intense public scrutiny of the numbers. Which experts, officials, and commentators have turned out to be trustworthy thus far? Which political leaders advocated opening up too soon, increasing the levels of infection for the sake of restoring the economy? Which were too cautious, risking the economy to prevent what might have turned out to be a relatively low number of severe cases?

We should expect that there will be no easy answers, with risks attached to most solutions.

The global outbreak of COVID-19 has changed our views of the world, potentially making it even harder to trust government authorities, media, businesses, and each other. Yet, recovery relies on trust. We need to trust that our employers are taking the measures necessary to safeguard us at work. We need to trust that retailers and our fellow shoppers and diners will do everything possible to prevent the spread of the virus. When a vaccine is made available, we need to know it works and that we can trust it not to have unacceptable side effects. And we need to know that our local and national governments and international health bodies are feeding us accurate information and offering sound advice. Until we establish this base level of trust, we will be unable to settle comfortably into any variation on the next “normal.” We also may need to accept that this new “normal” will feature a pervasive atmosphere of wary mistrustfulness.

When a vaccine is made available, we need to know it works and that we can trust it not to have unacceptable side effects.

We should expect that there will be no easy answers, with risks attached to most solutions. Consider the debate surrounding the development and implementation of COVID-19 contact-tracing apps—a digital solution that many argue can be effective in curbing the pandemic and minimizing future outbreaks. Despite the obvious benefits, there are potential pitfalls: What about privacy? Who will access the data? How can we ensure this access will not be abused? How can we trust the system to work?

These questions around trust call for a new level of transparency—a “show me, don’t tell me” approach to sharing information in real time, to demonstrating results and taking meaningful action to address concerns. And it has to be two-way—a mutual exchange that builds trust on both sides.

Opportunities and expectations for business to build trust

Businesses have a critical role to play in economic recovery and sociopolitical solutions because they are such dominant forces within modern society. As of 2018, 69 of the top 100 economic entities in the world were corporations, not countries, according to a global study by anti-poverty charity Global Justice Now. That level of might carries with it enormous responsibility—as well as heightened public expectations. Contributing to these expectations is the growing sense that all relevant actors in business, government, and civil society must work together if we are to succeed in handling the most significant global crises.

Much has changed since 1970 when the highly influential Chicago economist Milton Friedman laid out the doctrine that the sole “social responsibility of business is to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.” The past two decades have seen a growing number of companies, executives, and shareholders accept that business has a responsibility to do more than maximize shareholder value and make bigger profits. It must contribute to the greater good.

Consider, for instance, the leadership role Unilever is playing in regard to sustainability, Patagonia’s record of social and environmental activism, or Bank of America’s pledge to invest USD 1 billion over four years to help communities across the U.S. address economic and racial inequality. In an article in Harvard Business Review, Prof. Zeynep Ton of MIT’s Sloan School of Management illustrates the critical role retailers such as Costco and QuikTrip are playing in helping to rebuild the U.S. economy by creating better-paying jobs. Sector-wide initiatives are also taking shape, such as the 2019 U.S. Business Roundtable declaration, which acknowledged the need for companies to create value for all stakeholders—from shareholders and customers to employees, suppliers, and local communities.

It must contribute to the greater good.

Some corporations are going a step further, embedding this holistic mindset into their business strategy, with clear targets they are accountable for achieving and measurements that enable them to track and communicate progress. PMI is one example. We released our Statement of Purpose (SoP) as part of our Proxy Statement to shareholders in March 2020, reaffirming the company’s purpose of delivering a smoke-free future. PMI’s SoP also acknowledges that, as the company continues to transform its business and organization, its core effort to provide smoke- free alternatives that appeal to those adults who would otherwise continue to smoke will not be enough. We need to continue earning the trust and active cooperation of a host of stakeholders, from our supply chain partners to regulators and public health authorities.

Will this more holistic and socially minded approach enable businesses to build (or restore) trust? A closer look at what the public expects from companies today suggests the potential is there and spotlights opportunities for improvement.

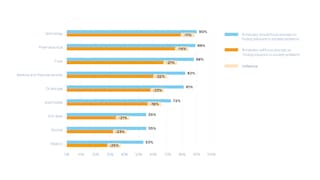

INDUSTRY RESPONDING TO SOCIETAL PROBLEMS—BY SECTOR

The online survey by Povaddo asked respondents which industries they think should focus on finding solutions to societal problems and which industries they think will focus on them. In other words, to what extent do they anticipate that their expectations of various industries in this regard will be met?

In the chart, the difference between the “should” and “will” survey responses can be regarded as a trust deficit metric. The smaller the delta, the smaller the degree of mistrust. The bigger the delta, the greater the mistrust.

The graph shows that the public expects the most from the tech and pharma industries. Given the timing of the survey, many weeks into the COVID-19 pandemic, it is not surprising that “should” scores are higher for these two sectors. While the alcohol and tobacco industries are at the bottom of the graph, it is worth noting that a majority of respondents believe both of these sectors should be focusing on finding solutions to societal problems, even if fewer than a third of the sample actually expect them to do so.

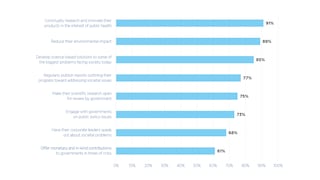

MEASURES COMPANIES SHOULD UNDERTAKE

The international survey also asked respondents to identify what specific measures they think industries should undertake.

The findings show that the public places the greatest importance on companies continually innovating their products in the interest of public health, reducing their environmental impact, and developing science-based solutions to the biggest challenges our world faces. There is also clear support for companies engaging more with both governments and the public on public policy and social issues, as well as expectations for companies to regularly report progress and make their scientific research open for review by government.

Looking ahead: Resetting trust in business

Even in normal times, trust takes years to build and can be undermined in an instant. Today’s abnormal reality—the pandemic mixed with sociopolitical upheaval and intensified polarization—adds further complexity for businesses seeking to earn trust from a broad swath of the public. Understandably, some businesses might be tempted to remain on the sidelines for the duration, studiously avoiding controversy and steering clear of hot-button issues. The evidence is abundant, however, that the sidelines are no safe place for big businesses in 2020 and for the foreseeable future.

To understand how current events are affecting corporate reputation, business management consultancy High Lantern Group analyzed 1.6 million tweets by some 3,000 leading activists, policymakers, news organizations, and businesses in the 90 days leading up to April 20, 2020. The study found that businesses’ response to the pandemic has unseated climate change as the number one issue affecting corporate reputation. Importantly, there are several vital components tied to pandemic response, including policies in place to protect workers (e.g., paid sick leave, employee healthcare coverage, and workplace safety), supply chain continuity, and price gouging. Companies are expected to go well beyond meeting their baseline obligations to protect customers and employees and contribute to pandemic- mitigation efforts.

The evidence is abundant, however, that the sidelines are no safe place for big businesses in 2020 and for the foreseeable future.

Globally, businesses have been answering the call to action, pivoting in the early weeks of the pandemic, for instance, to produce vital medical devices and personal protective equipment, helping to shore up jobs, and creating digital solutions to help public health authorities track the spread of the virus. In the U.K., a team of employees at AE Aerospace worked 24/7 to produce 6,000 complex ventilator parts in less than two weeks; this compares with a usual pace of producing 2,500 aerospace parts a month. The global logistics firm UPS, through its foundation, bolstered its cooperation with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, to strengthen supply chains so vaccines can reach isolated communities around the world. Inditex, owner of fashion chain Zara, repurposed its textile factories to manufacture scrubs for hospitals in Spain.

How should these experiences shape business action and focus moving forward?

“Virtue is its own reward” may be a tough sell to the company board, let alone to shareholders. But doing the right thing consistently over the long term is how companies earn trust among consumers, media, and public authorities. As Miller and Thate wrote in their paper: “The processes and practices of trust must never rest solely at the level of obligation and compliance. […] Organizations must seek to live, move, and have their being within the very structures of trust. That is, organizations must enact the language, culture, and practices of trust so as to demonstrate their trustworthiness beyond mere obligation and contract.”

In other words, an organization that wants to be trusted must commit to being trustworthy— not just because the rules demand it, not just because it is good for business, but also because it is the right thing to do.

Businesses and their leaders can help restore public trust through the actions they take to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and to address other pressing societal concerns. But this will require that they act as a genuinely beneficial force, with competence and integrity, to create positive impact beyond their usual activities and value chains. The companies that realize this is not a one-off exercise and rise to the challenge by meeting society’s expectations in an authentic and consistent way ultimately will be the ones to build and sustain trust over the long term.

Aaron Sherinian, PMI's VP Global Communications Transformation, talked with Marta Belcher, Chair Filecoin Foundation, and Bruce Degn, Executive Director Industry Transformation Coalition, about the importance of transparency when restoring trust. Watch their discussion below.

Part one:

Part two:

© Philip Morris Products S.A. 2020